April 16, 2001

By Rochelle Sharpe

For a while, becoming fabulously wealthy practically overnight seemed to be about as easy as waking up in the morning and getting out of bed. That's the way it was for Jon Simmons of Fontana, Calif., who turned a measly $4,500 into $2.2 million in just 13 months by investing in Internet and other tech stocks. When he hit the $1 million mark early last year, he quit his job as a computer programmer and concentrated on trading. Two months later, when his stocks had more than doubled, the 31-year-old began to fantasize about buying his dream home--just as soon as he doubled his money again. He never got the chance. Within days, the tech stock bubble burst and, after paying his taxes on earlier gains, Simmons was left with just $100,000. His wild rise and sudden fall left him dazed. Often, he had to remind himself: "It was just money."

Maybe for him. But many investors have lost a lot more than paper profits during this long and seemingly bottomless slide. A year after the peak of the Internet-driven stock frenzy, what one psychologist calls "the fear-greed roller coaster" has drained bank accounts, delayed retirements, pulled marriages apart--and worse. A New York couple, who suffered enormous losses through day trading, entered into a murder-suicide pact last fall. George Schavran, 70, shot 42-year-old Catherine Fischer and the couple's German shepherd, Graf, on a desolate Long Island beach. He survived his suicide attempt and now faces a murder charge.

Only now is the full extent of the damage to personal finances and people's lives becoming clear. Since the market's peak, $4.6 trillion of investor wealth has vanished. In just one year, the number of millionaires plummeted more than 10%, from 7.1 million to 6.3 million, according to the Spectrem Group, a Chicago-based consultancy. If that wasn't enough, many people are being forced to pay taxes on capital gains they no longer have. They sold stocks near the peak and reinvested in others as the market was sliding to new lows.

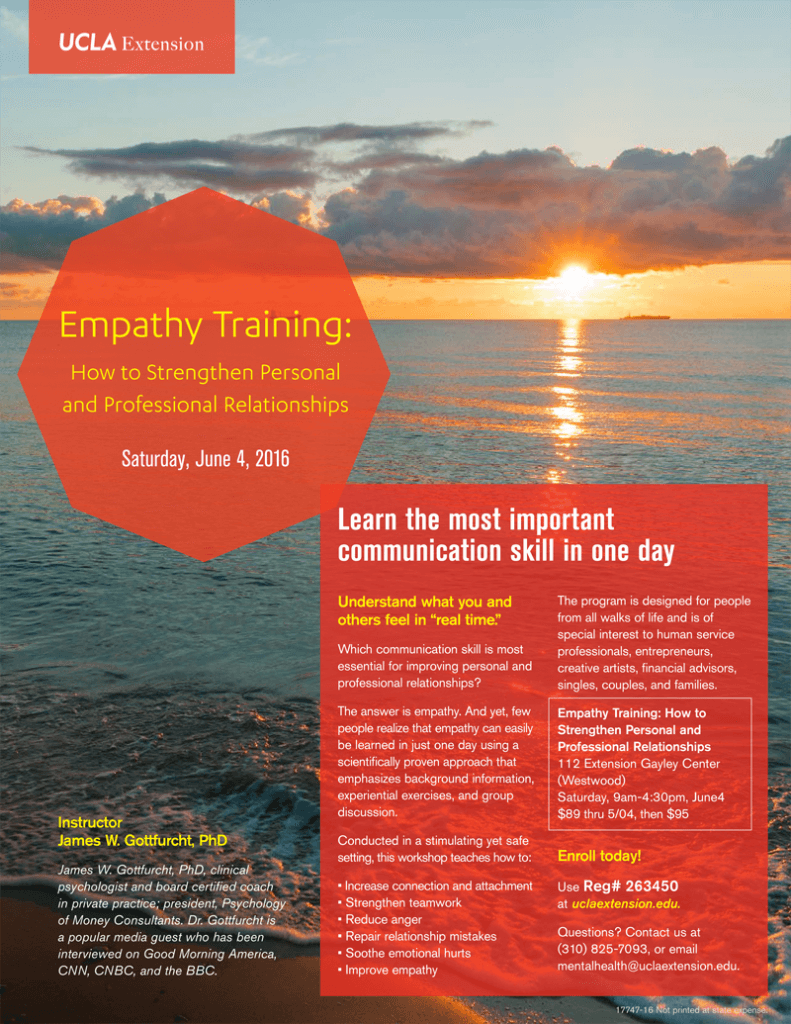

The rapid swing between instant wealth and financial worry produced emotional whiplash. The thrill of counting out Nasdaq profits has been replaced with bitter hours of fear and self-blame. For some, "It's almost like dealing with death," says James Gottfurcht, a psychologist and president of Psychology of Money Consultants in Los Angeles. Investors are grieving--passing through stages of denial, anger, and depression. The sad reality, psychologists say, is that the pain of losing money is far stronger than the pleasure of making it. "I feel absolutely devastated by my lack of good financial judgment," says Roy DuBrow, owner of a Seattle limousine company, who lost about $700,000 in paper gains on tech stocks.

Uncertainty principle. People need to learn to cope with such feelings or they could end up compounding their problems. "If you don't deal with these things, you begin to act out," says Kathleen Gurney, CEO of the Financial Psychology Corp. in Sonoma, Calif. "People start to do irrational things," she says, like buying an expensive car they can't afford in an attempt to blunt the emotional pain. Seeking help from therapists and financial advisers can keep things from getting worse.

The hurt isn't limited to individuals. A sharp drop in consumer confidence has contributed to the steep downturn in the economy, and seems likely to affect investing for months, maybe years, to come. Without a belief that stocks will achieve even pre-frenzy returns, investors won't likely place bets that could help produce those returns for everybody. Instead of a virtuous circle, the pattern of positive reinforcement is broken--replaced by fear, uncertainty, and mounting financial losses. "My fear is that you'll see people pull out of the market and never invest again," says Gurney.

The allure of Wall Street was hard to resist--and practically everybody who could scrape together a handful of savings gave stocks a try. By the end of 1999, nearly 80 million Americans owned stock, compared with 42.4 million in 1983, according to the Investment Company Institute. Getting rich quick was no longer just the stuff of Super Lotto dreams. Thanks to tech stocks and the seemingly limitless promise of the Internet, it looked like the old rules had been suspended and any schmo could become wealthy. Indeed, Spectrem says, there were 3 million more American millionaires in 1999 than in 1995.

The ride was dizzying--both up and down. Take DuBrow, the limousine company owner. At one point, DuBrow, 62, was nearly a millionaire, having watched his $100,000-plus bet on Net and tech stocks skyrocket 800%. He became addicted to the market. He started talking to his broker five times a day and became glued to CNBC. For a while, his obsession made him feel great. "I began to feel like a guru," he says. He would talk excitedly to friends about his latest successes. On his best day, he was up more than $45,000. "I felt like I was almost at the cutting edge," he says.

When the market declined, his confidence evaporated. For the first time in his six-year marriage, he hurt his wife, Anita, grabbing her arms and shaking her briefly when he lost his temper. Normally, she says, "He's such a gentle person. It scared me half to death to see him change that much." Sounding despondent in early March, DuBrow talked about going cold turkey and selling everything. Just days later, his mood had swung to the other extreme. He was convinced that the market had hit bottom and could only go up from there--and he was buying again.

The meltdown market was especially jarring for people who worked for dot-coms. Often they were hit by a double whammy: trying to deal with the shock of instant wealth, and then, just as they were preparing for their new life, watching their money vanish. One 28-year-old Yahoo! Inc. (YHOO ) exec who had spent two years searching for the perfect mansion not only bought his $2.5 million house but also paid his taxes with margin loans, says Pat Ingraham, a Century 21 real estate agent in Saratoga, Calif. When Yahoo's stock began to collapse, the man was forced to sell the house before he moved in.

Some tech workers are winding up with huge tax bills and little money to pay them. Fran Maier, 38, former senior vice-president of marketing at women.com (WOMN ), in San Mateo, Calif., exercised more than 60,000 stock options when they were worth $6 a share, up from her grant price of 80 cents a share. Maier had to pay taxes on the gain in 1999, even though she hadn't sold her shares. In fact, she was barred by law from selling them for six months, but by that time they were sinking. To get enough money to pay her taxes, she had to sell shares at $3 each and take a second mortgage on her home. "It feels awfully bad to pay taxes on gains you never saw," she says.

Such financial ups and downs take a heavy toll on families. When Maier's son was asked by his fifth-grade teacher to write an essay about what he'd do with $1 million, he wrote that he'd give some money to his mother so she could pay her taxes. It gets worse. A California woman who asked to go only by her first name, Mary, says sudden wealth ruined both her marriage and her financial dreams. Her family's assets had skyrocketed by $25 million overnight when her husband's tech company was bought by another one with a high-flying stock price and he received a large grant of shares. Three months later, Mary was shocked when her husband took her out to lunch and announced he wanted a divorce. She believes he saw his newfound wealth as the opportunity to lead the life of a rich playboy. While the marriage fell apart, the stock price did too, tumbling from a high of $250 to $53 a share before she sold.

Compounded mistakes. Even people who took relatively small risks are paying the consequences, being forced to postpone their retirements or purchases of homes. Arthur Rubin, 53, of Ashland, Mass., transferred $50,000 of his assets into the QQQ Nasdaq 100 tracking stock in early 2000, buying in when the stock was $107. "When it started going down, I got excited," he says, seeing it as an opportunity to buy more. He bought more stock when shares were in the 90s, and then in the 80s, then stopped his buying spree as the stock continued to sink to $53. Now, he says, his dreams of early retirement must be delayed.

It may seem a little late, but many stunned investors are now seeking help from financial planners. The profession has watched demand increase by as much as 40% over last year. Gary Schatsky, chairman of the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors, recalls the man who came into his office looking for advice--his hand shaking uncontrollably. The 29-year-old had lost 60% of his $1 million inheritance in just two weeks, Schatsky said. He had relied on a broker who convinced him to place all of his money in technology stocks.

Some people who have hit bottom are seeking help for depression, anxiety, and self-esteem problems. Psychologists teach them to cope with what has happened to them, and to do a better job of sizing up their ability to take risks in the future. Gottfurcht says frazzled investors could have saved themselves a lot of heartache if they had kept a careful watch over their emotions when times were good. Idealization, for instance, can cause a person to put a company or stock market guru on a pedestal. Denial can lead to a person refusing to believe that the market has changed course, despite strong evidence to the contrary.

To protect people from falling into what he calls psychological money traps, he suggests investors write down their financial goals for a stock when they purchase it. With a written record of their original intentions, they may be less likely to get drunk on greed and stay with a stock too long. And he urges people to find a friend to play devil's advocate concerning their stock picks. That can help guard against irrational optimism.

In spite of all the horror stories--some investors cling stubbornly to their dreams of Net-stock riches. Ron Peloquin, 42, of Windsor, Conn., bought shares of Internet holding company CMGI (CMGI ) for $3.50 in 1998 and watched the stock climb to $330 in two years, turning $70,000 into $1.1 million. He held onto most of his shares, even though the price has slid below $3. In fact, now that it's so low, he has started buying CMGI again. Although he quit his job as a computer programmer when he became a paper millionaire, he recently returned to work--so he can afford to buy stock. Like many true believers, he's convinced that most people have overreacted. Now, he's patiently waiting for the market to rekindle its love affair with technology, and when it does, he'll be there to reap the rewards. That scenario seems highly unlikely, at least in the short term. But, if Peloquin's right, get ready for another bruising ride.

Search for